A peak NSW nursing body has thrown its support behind a campaign to decriminalise abortion in the state.

NSW Nurses and Midwives’ Association (NSWNMA) is one of 70 signatories of the NSW Pro-Choice Alliance, a campaign launched by the Women’s Electoral Lobby in early May. Other signatories include family planning centres, women’s health centres, lawyers groups and domestic violence prevention groups.

After an historic vote in Queensland parliament late last year, NSW remains the only Australian state which has yet to legalise abortion. Under sections of the NSW Crimes Act, enacted 119 years ago, women who access abortion and health practitioners who help facilitate this choice are criminals under law. While there have been no prosecutions in recent times, the potential penalty is up to ten years imprisonment.

The only circumstance which gives exception to criminality is if a doctor is of the honest opinion that “the operation was necessary to preserve the woman involved from serious danger to her life or physical or mental health which the continuance of pregnancy would entail”. 'Mental health' has since been interpreted to include “the effects of economic or social stress that may pertain either during pregnancy or after birth”.

Irrespective of this leeway, NSWNMA general secretary Brett Holmes contends the law violates women’s reproductive rights, infringes their autonomy, and places an unfair burden on both patient and provider.

“Abortion is a health issue, not a criminal issue," Holmes told Nursing Review.

“Firstly, we believe in the right of patients to self-determine the health choices they make. And we particularly believe that women should have a choice to decide on medical issues around their own body.”

These women deserve to be cared for by professional staff, he continues, who do not feel they are risking their professional or personal lives by assisting a patient in need. This encompasses not only the risk of criminal prosecution, but “their right to provide services and expertise”.

Indirectly, those involved in ethical abortion procedures may be emotionally, professionally and psychologically harmed through social prosecution, whether that be “intimidation or threats of attacks from well-meaning but misguided people trying to change minds that have been already made up”.

Safety and privacy measures to mitigate this harm were introduced last year, when NSW parliament made it illegal for protesters to harass people within 150 metres of clinics and hospitals that provide terminations.

Under the current arrangements, NSW nurses approached by women seeking abortion must refer them to another service – the vast majority of which are privately run. This, says Holmes, further punishes and alienates both women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and women living in regional or remote communities.

To afford this private service, and potentially the travel cost on top of it, such women may be forced to negotiate a loan from Centrelink. This notoriously impersonal and occasionally bungling bureaucratic program subsequently becomes the arbiter of this very personal choice at an intensely time-sensitive and pivotal moment.

“If they're unemployed, then they've got to spend months, if not years paying that advanced payment back,” says Holmes.

“This is a cruel way to deal with people in crisis … Whilst the legislation doesn't guarantee that that would occur, the public health system seems to have de-risked itself by not undertaking this health procedure.”

“Any woman who has to make this choice shouldn't be unnecessarily punished or impeded by our laws or our health system.”

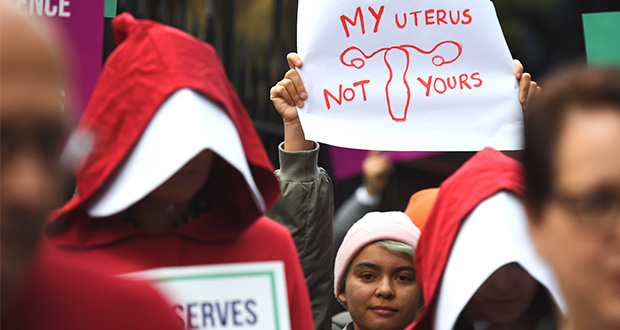

The debate around abortion has flared up in recent months, as states across America take a progressively hardline approach on the issue, emboldened by a Supreme Court newly weighted with conservative justices.

Four US states have so far adopted the ‘heartbeat bill’, which bans abortion before a woman may be aware she is pregnant. As reported by the Chicago Tribune, in Ohio, an 11-year-old carrying her rapist’s child is not eligible for the procedure. Alabama’s Human Life Protection Act, signed in May, bans abortion completely, even in the case of rape or incest. Any doctor who performs an abortion there could be sentenced to up to 99 years behind bars.

Holmes acknowledges that in Australia’s last conservative pro-life stronghold, the issue remains divisive. One NSWNMA member has resigned after the association made its stance clear.

“But it comes down to principles about choice and rights and dignity of people,” said Holmes. “Principles are principles and hopefully more people will join than leave.”

He is also convinced that the majority of the public would like to see the legislation brought into the 21st century, with parliament reflecting a minority of “louder voices who are passionately against giving women the choice on how to manage their own bodies”.

This view is backed by research conducted by the University of Sydney and James Cook University in September last year, through a survey involving 1000 NSW residents. 73 percent of respondents thought abortion should be decriminalised and regulated as a healthcare service.

The survey also found, however, that 76 percent of respondents were unaware that abortion is a criminal offence in NSW.

One in three Australian women will have an abortion in their lifetime, with 80,000 carried out each year across the country.

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source